My Journey to Contemplative Photography is about the growing conflict with the contemporary approach to photography. 1

The strong desire to find a way out of this impasse motivated me to explore new horizons. Let me tell you how it pushed me along the way and helped me to embrace a new way of image-making.

Then I’ll look at the contemplative approach from a Zen Buddhist perspective. Lastly, I’ll talk about my experience.

I got serious about photography when I retired, when I joined the Montreal Camera Club. However, after a few years I left because I felt I had reached a plateau but did not know where to turn to. I had become dissatisfied with the commercial, conceptual approach, with its emphasis on technique, equipment, subject matter and competition. Of course, I much appreciated getting better technically, and doing well in competitions was a lot of fun. It boosted my ego but did little for creativity. I began to feel something fundamental was missing.

Transition

For a few years I searched for an alternative. It was in 2013 when I accidentally stumbled upon a course, entitled Contemplative Photography. I jumped at it because of my training in Zen meditation. The course was offered by Michel Proulx who was a teacher at Marsan College of Photography. It opened a door, providing me with a practical starting point. I was hooked because I finally could see that there was a way to apply zazen to photography. Since then I have explored the contemplative approach from a Zen perspective. However, the switch was difficult and painful at times. I struggled with it for a long time and still struggle with it but it has become easier. What makes it difficult is the fact that we identify so strongly with our habits of seeing. Once they are established, they are difficult to change. We believe our way of seeing the world is the right and only one, and if challenged, we defend our position as if it were the absolute truth.

Let me show you how my images changed drastically during this period of transition. Here are seven pictures of the past:

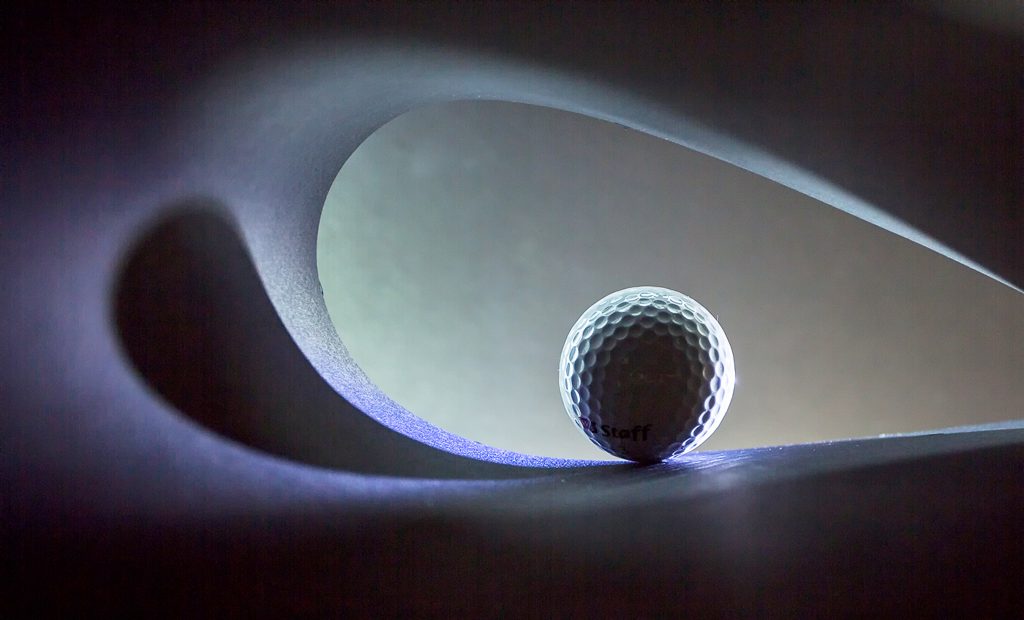

In contrast, the image below is an equivalent of one of my first flashes of perception: It marks the break with my past photography.

I chose this image because it shocked me, it shook me up like no other. For a while there was confusion; everything seemed to have turned upside down. Letting go of old habits and values was painful. I found the blackness overbearing, I felt it was not me nor mine. I rejected it – initially. At the same time this direct experience was very energizing. It opened my eyes. I could see my photography was pointing into a different direction.

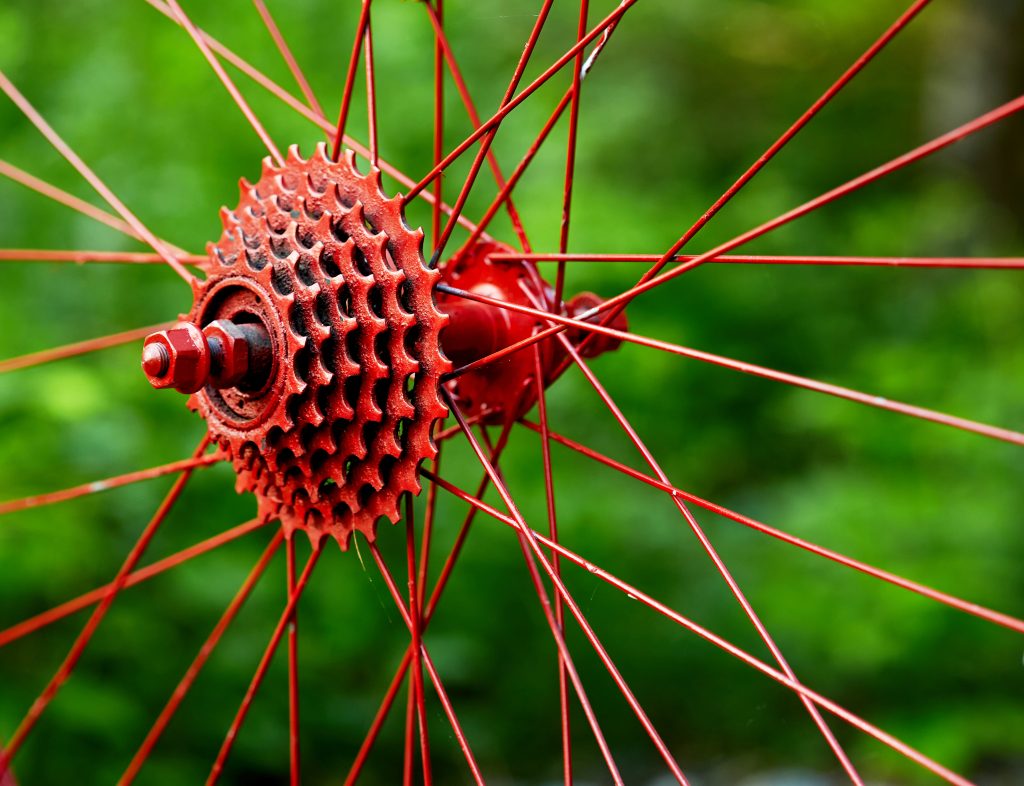

Here are seven images that mark the contemplative approach:

Something else happened during this transition: I began to sell most of my equipment. In hindsight, I think, what happened was that I stopped pretending to be a photographer.

A few years later, in 2016, I started this website where I began to post images and articles on a regular basis. More recently, I have revised these short articles and published them in a small book with the title Seeing with Your Own Eyes.

What draws me to Contemplative Photography?

What I find most attractive is the emphasis on the quality of “seeing”. It is about the capture of images at their inception – before concepts begin to impose themselves and take over. On one hand our amazing capacity to think conceptually is essential to function in life. On the other hand, seeing the world through concepts only, separates us from living fully and stops us from seeing clearly. Let me emphasize that the aim of a meditation-practice is not about getting rid of concepts or techniques. It is about loosening the attachment to our conditioned, conceptual way of seeing. Liberated from these limitations one feels relieved and energized. There is little written about how to open up to “just seeing” and how to deepen it. I believe this approach to “seeing” is at least as important and valid as knowing how to take a picture technically. Some suggest, in the light of all the technical progress, that we are “seeing” less and less.

The emphasis on “seeing” and not on technique is not new. It is something that many of the old and new masters of photography have emphasized (Stieglitz, Minor White, Edward Weston, and many others). Henri Cartier-Bresson2, for example, emphasized explicitly the experience of “seeing”. He felt that thinking should be done beforehand and afterwards – never while actually taking a picture. He was very much aware that a seeing that comes primarily from your head is contrary to life.

The non-conceptual approach to seeing is a constant challenge because it demands that we are fully present – not just with our eyeballs. It is an integrated response that affects all our senses, body and mind. It happens when something stops us in our tracks or when we are captivated by what we see. This way of seeing is alive and vibrant.

For me this is the climax of this process and more important than the actual image. The lasting satisfaction and fulfillment come from being one with what you see, when you are able to forget yourself, when seeing means forgetting the names of the things one sees. Then, you are no longer separate, you are whole and fully alive. The distinction between subject and object drops away. When everything comes together seamlessly, it creates a feeling of oneness – a powerful experience that you would like to have again and again. Hisamatsu, in his book on Zen And The Fine Arts 3, describes this profound experience very well when he says “The tree is still a tree, but now it is a wonderful tree”.

The key element of the contemplative approach

As mentioned before, the crucial element or the “way in” is one’s ability to be present. It requires a mind that is highly attentive and quiet – free of distractions. Then we can be “one with”, with what-ever we are seeing or doing. Who and what we are drops away momentarily. Our mind is open and alert which sets the stage for creativity to flow.

The “flash of perception” is such a natural, spontaneous moment of non-distraction. It is a gift of the moment that has no past, no future. It is a seeing that is immediate – before the processing, reflecting mind kicks in, before we understand what we see, before we start labeling and judging (perception precedes conception).

Does one need to be a Zen Buddhist to experience what it means “to be one with”? Of course not. All of us have been involved in peak experiences of “oneness”, when one forgets everything around oneself. Making love, for example, is one of them or when you suddenly find a creative solution to what appeared to be an intractable problem. Inventions are often made by these sparks of creativity. Other examples that show what it means to be “one with” are high performing athletes: when they are in the “zone” or “in flow” they lose themselves and do amazing things that look deceptively easy and simply. You can’t fabricate, imitate or fake this kind of simplicity because it is alive and authentic.

However, creativity comes with a price. It’s not just pure joy all along the way. It is not just about having fun and a good time. The joy involved in our creative endeavors does not come without risks and struggles. Before we can experience the flow of creativity we have to free ourselves of what distracts us. This takes some work on our part because it is not easy to suspend our personal self that is so strongly invested in our feelings, believes, opinions, prejudices and judgements.

The practice itself

We can’t work directly on “flashes of perception”. They are unpredictable; but we can facilitate their occurrence by being present with an open and receptive mind.

This sounds very simple but it does not mean it’s easy. Most of the time we are not fully present because our minds are too busy. Constantly, we are bombarded by thoughts, feelings, images, ideas, conflicts, expectations and so on. These distractions can’t be let go simply by good intentions or strength of will.

When I go out to photograph I allow myself to be surprised by what captures my attention. For example, when I am in the countryside I drive around in my car at a very slow speed – usually on gravel roads. I lose myself in “just seeing”- without focusing on anything in particular. This distinction is important because focused seeing is limiting. It confronts us with objects, forms and shapes and emphasizes a seeing that is objective (conceptual) which reduces us to spectators, looking from the outside in, flattening the depth of experience.

In contrast, I practice non-focused seeing by just following the gaze of my eyes, letting them touch whatever they see.

It is important to be aware of one’s peripheral vision. Stimulation of the visual periphery adds richness to one’s seeing from within. It connects one intimately with the surrounding space. It adds flesh to your image. Whatever your eyes touch, you refrain from labeling, interpreting, self-reflecting or judging. When thoughts, feelings, ideas come up you acknowledge them and let them pass but you don’t chase after them. If you treat them like uninvited dinner guests and don’t feed them, they fade away. You just return simply to “seeing”. With this approach, the mind settles and gets quiet, preparing favorable conditions for a flash to occur.

Flashes come in a variety of forms. They may be brilliant or you see something from the corner/periphery of your eyes that catches your attention, or it comes in the form of a sudden connection that clicks into place. Frequently I tend to dismiss what I see from the corner of my eyes. Now, when this happens, I go back to it, explore it and stay with it. Often it turns out to be a flash. You know when it happens. You can’t miss it. When a connection is established, waves of resonance between the subject and oneself flow back and forth. We stay with it as long as possible. During this event I make several exposures until these moments fade away.

Images that are the outcome of these special moments are often described as shockingly simple, fresh and new. You may wonder why you have not seen it before, since it has been there in front of you all the time. Seeing what is there in a new light lends a certain quality to images that is usually not seen. The content of the flash is incidental. What stays and is most satisfying and fulfilling, is the process of connecting more deeply with oneself.

Conclusion

If one is happy and satisfied with one’s photography there is no good reason for changing. Without dissatisfaction there is no motivation to go through the trouble of changing one’s approach. It would just turn into another technique. But contemplative photography is not a technique.

However, when you are conflicted about your photography and it wakes you up during the night, don’t ignore it. Allow the conflict to become a motivator for change to happen. Stay with it and explore it! It will activate your inherent creativity and help you to discover new avenues until you find what is right for you.

Notes

1 This article is based on my presentation at a virtual conference on Contemplative Photography. It was organized by the Montreal Camera Club and held on December 2, 2020. The moderator was Michel Proulx, a professional photographer. He was also, with Sacha Marie Levay, a co-presenter.

2 Quoted by Andy Karr and Michael Wood in The Practice of Contemplative Photography; p.5; Shambala; Boston & London; 2013

3 Hisamatsu Shin’ichi; Zen And The Fine Arts; p. 52; Kodansha Int. Ltd; 1982